Writing Across the Curriculum: Making Your School the ‘Write’ Place

A P.E. teacher and a math teacher walk out of a faculty meeting…Sounds like the beginning of a joke, right? But here’s the rest of the scenario:

The math teacher shakes her head, “I don’t know what’s going on in the principal’s mind. Writing in every class? That’s ridiculous!”

The P.E. teacher replies, “Yeah, what are we supposed to write about in my class? The history of dodge ball? I’m sure some of my male students could write an excellent essay on why they enjoy watching the girls run laps…”

The math teacher laughs. “I’m sure they could! I think that the English teachers are just trying to cram their curriculum down our throats. Don’t they know we have our own curriculum? I think they’re bribing the principal!”

“Students don’t even bring pencils and paper to my class! They’ll rebel if I even ask them to! I’m just happy if they remember to bring a change of socks and running shoes!”

“And the grading! Like I have the time to grade a hundred essays. If I do writing in my class, then those English teachers should have to do math problems in their class!”

“And jumping jacks!”

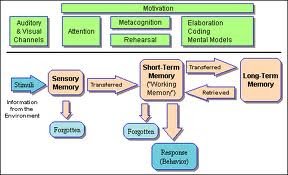

If you have ever tried to initiate any school wide program that involves writing across several contents or writing across the curriculum, perhaps you have heard or participated in conversations similar to the conversation above. Some teachers see these programs as just one more thing on their already-overloaded teaching plate. Others see it as an overwhelming task that doesn’t pertain to their classroom. When an administrator stands in front of his/her faculty and simply announces that students will be writing in all classes, this program is bound to fail. It is true that writing is important in more than just the English classroom because, one, the more students write, the better they become as writers and, two, writing is a thinking skill and communication skill that is essential not only in school, but in life. Writing is also a universal learning tool that can be used in any classroom to teach any content and to help students be metacognitive about their learning. If it weren’t beneficial, schools across the nation wouldn’t be trying so hard to incorporate some sort of school-wide writing program, right? So why do so many schools flounder with writing across the curriculum programs? Why do so many teachers resist such a program? How do we make writing across the curriculum work?

Good questions. I don’t assume to have all the answers or a sure-fire way to fix all of the educational problems in the world, but when it comes to writing across the curriculum, the following suggestions will make school-wide writing less daunting for teachers of all contents and more effective and beneficial for students. To make writing across the curriculum work, first all teachers need to understand that not every piece of writing must be read and graded. Second, all teachers must be writers to some degree themselves. Third, teachers need to differentiate between content literacy writing and writing to learn and use both in their classrooms.

Not every piece of writing must be read and graded by the teacher.

“If the amount kids write is limited by what teachers have time to grade, there’s no way they’ll write enough to learn curriculum content” (Strong, 2006, p. 33). In reality, students should be writing every day. For this to happen, they need to have opportunities through out the day to write about different subjects and in a variety of genres—it cannot only be happening in the English classroom. With all of this writing, I’m guessing that not all teachers want to dedicate hours of their personal life to grading student writing. Surprising to students but true nonetheless, teachers indeed have a personal life, so why are we, along with our students, holding onto this image of hours of toiling over papers, red pen in hand, when that isn’t the most effective method? Even English teachers need to let go of the idea that every piece of student writing must be inspected by a teacher, like pillows on an assembly line with a tag attached to them saying who inspected them. Whether or not we grade a written assignment or the amount of time spent grading writing depends on the purpose of the writing. Was the writing assignment designed to help students learn a certain concept, to help students remember what they’ve learned, or to improve their writing skills? Some writing assignments may need a simple check off to know that the student completed the assignment. Other writings need only to be shared with the class or a partner. Maybe another writing assignment can be used to help students on a test.

In his book Write for Insight, William Strong (2006) gives an example of a fellow teacher and colleague who "used writing-to-learn in all kinds of ways--to open class, to explore concepts during class, to summarize learning at the end of class, and to anticipate reading for tomorrow’s class. Students often swapped papers and responded in dialogue fashion to each other’s ideas. All of this written work was ungraded, but points did provide an incentive for staying on task” (p. 34).

This was in a biology classroom. Notice that at no point did the teacher say, “I took home all of their 4-page essays and spent my entire weekend reading and grading them.”

We need to start look at writing assignments more as learning and thinking tools rather than weapons of mass assessment. In Vicki Spandel’s book The 9 Rights of Every Writer (2005), she states:

[Writing across the curriculum] is not usually (and should not be) assessed, but it needs to happen because it helps students use language to think clearly. We assume we know what is going on inside our own heads until we are challenged to put it on paper. That simple act brings us face to face with the fuzziness in our own thinking, the blank spaces and looming holes, the missing connections…When we read, we take in information. When we write, we refine it (p. 71-72).

Some examples of writing assignments that don’t necessarily need to be read and graded by the teacher are learning logs and journals, admit and exit slips, short writing spurts (for example, “take out your notebooks and write what connections you can make to this.”), note-taking, etc. If the sole purpose of the writing is to help students learn and remember what they learned, then the act of writing itself is enough. Imagine if every bit of writing you did was graded. How frustrating would that be! An email sent to your mother, a text to your best friend, a grocery list, a note to your principal, a thank you card for your neighbor…think how frustrating it would be to have the thank you card returned with red corrections all over it and a grade at the top! We need to move our students away from writing for a grade towards writing to learn, writing to communicate. As Deborah Dean states, “Students need to see that this writing is not an end in itself but an avenue to learning…” (2006, p.34).

All teachers need to be writers to some extent.

You’re shaking your head. Not only do English teachers want you to make your students write, but now they want you to write? When will they stop? Is it ever enough? Before you stop reading in disgust, let me explain. I’m not suggesting that every teacher sit down in a corner and write a poem or a novel. However, everyone writes in some form or another. Scientists write reports of what they found in their research and experiments. Mathematicians write how to solve an economic problem. A historian may write an analysis of a historical event using the primary sources gathered and studied. An artist may write a descriptive piece about his/her art in order to enter it in an art show. In our day-to-day busy lives, we all write—memos, notes, thoughts, lists, etc. If we didn’t write, we would still be stuck trying to figure out how to start a fire or make a round wheel!

Our students need to see their teachers writing and not just their English teachers. “When what you know about ‘people who write’ becomes what you know ‘as a person who writes’, what you know changes” (Ray, 2006). When you are able to look at yourself as a writer, you will be able to incorporate writing into your classroom learning more effectively. When you can stand before your class and write with them, your teaching will be empowered. As teachers, we shouldn’t be afraid to model writing for our students. It’s okay for students to see their teachers struggle sometimes too. We all have struggles to find the right words or to get our thoughts to mean the same on paper as they did in our heads. Students need to understand that this struggle, this process is human and that we, as teachers, are human. Imagine if students went to their seven classes each day and saw all seven of their teachers as writing models in some way. Imagine the shift of attitude that could come as students begin to see writing as needed for learning rather than just assigned for grading. That shift of attitude has to start with us first.

So how do you become a writer if the last thing you really remember writing was a report back during your glory days of college? First, take out a piece of paper and brainstorm any writing that you do, even if it’s something scribbled on a post-it-note, it’s writing. Next, brainstorm and list the kinds of writing that might be done in your field of study. This could be a great activity to do with your students! And then, after all of this brainstorming, challenge yourself to incorporate more writing in you day-to-day activities and to try new kinds of writing. Remember, no one is asking you to write a novel (not yet anyway…).

Teachers need to differentiate between content literacy writing and writing to learn and use both in their classrooms.

The third way that we can make writing across the curriculum work is to realize that there are two main types of writing in a content—content writing and writing to learn. If teachers can differentiate between these two types of writing, they can find new and more effective ways of incorporating writing into their contents.

I once had a Spanish teacher come to me with some concerns. At our school, every teacher was required to assign one writing assignment in their class once per quarter. It was nearing the end of the quarter and this Spanish teacher had forgotten to assign the writing piece. “I was going to have them do some mini-reports on Spanish-speaking countries, but we completely ran out of time!” I walked into her classroom and found her students working in pairs, writing something.

“What are they doing right now?” I asked.

“Oh, they’re just working together to write out a simple dialogue in Spanish which they will then perform in front of the class. We’ve been working on basic greeting phrases and what to say when you first meet someone.”

“Why can’t this assignment count as your writing piece? They’re writing aren’t they?”

The Spanish teacher stared at me in disbelief. “It’s really short, and it’s in Spanish! I don’t think that this is what the English teachers would approve of!”

With content writing, we must ask ourselves what literacy looks like in our content. What does a mathematician read and write? What does a scientist, an artist, a musician, a historian, a physical trainer read and write? Sometimes some content-area teachers try to give writing assignments that they think will make the English teacher happy but don’t really have anything to do with their curriculum. Their thought is, “I’ll just have my students write this report/essay/poem, so that the principal and the English teachers will leave me alone.” The assignment ends up being disconnected from the students’ learning and thus unimportant to the students and the teacher. It becomes just something else on an already full plate. But writing is everywhere—in math, science, art, music, history, P.E., technology—everywhere! Writing can look very different, however, depending on where you find it and what its purpose is. In a business memo, a businessman may be proposing a new plan using numbers and statistics (math writing) to show why this plan would be better for the company. Or a scientist might be writing to report the results of an experiment he/she just conducted and how these results will affect the world (science writing). A dietician may write a new diet plan for someone recently diagnosed with diabetes to help him/her develop a healthier lifestyle. Content writing is often over-looked in our classrooms. Granted the English teachers just love those acrostics being done in math, but the reality is that the majority of our students will not go on to have careers that involve writing poetry or short stories about the life of a cell. They will be doctors, business associates, lawyers, teachers, entrepreneurs, government officials…the possibilities are endless. Our students are always asking how what they are learning in class has anything to do with their lives. Colleges and universities are asking schools to better prepare students for the academic world where we will send many (as many as we can) of our students. Future employers are begging schools to produce better-prepared employees, people equipped with the thinking and communicating skills needed for the world at hand. We are doing a great disservice to our students when we don’t offer this variety of real-world, applicable writing to them in our classrooms.

Another reality is that only specific content teachers can teach content writing. A couple of years ago, I decided that I was going to teach my reading class, a group of struggling readers, how to read like a mathematician. I figured that many students struggle in their classes because they lack the literacy skills to learn and do the skills required for that content. If I could get them to think like a mathematician, to understand how to read like a mathematician, then they wouldn’t struggle so much with math. Here’s my background: I struggled through math my entire life. In high school, as a senior, I took algebra II again so that I wouldn’t have to take calculus. In college I took the minimal math class that a couple of years later, the college deemed not sufficient to meet the math general credit requirement. My husband jokes that I’m the only person with a Master’s degree who believes my bank statement is written in a foreign language, I try to read it, and I fall apart. Math is my kryptonite. And so with that background in mind, try to picture what it was like trying to teach math literacy in my classroom. To say the least, it was a complete failure! I wrote a rap about thinking like a mathematician, I had the students bring their math books, and from there it went downhill. That’s when I learned an important lesson: Students need to learn content literacy in their content classes. I wouldn’t hire an artist to do my taxes nor would I hire an accountant to paint a portrait of my family. Each teacher is the expert in his/her own field and it up to each teacher to teach his/her content literacy (reading and writing) in his/her classroom.

Another form of writing found in the classroom is writing to learn. This is where the math acrostics and writing a narrative about the life of a cell come in. Deborah Dean defines writing to learn in the following manner: “When you write to learn, you are not trying to show how well you write or how much you already know about a topic; you are writing to learn more” (2006, p. 33). Writing to learn activities have the specific goal of using writing to help students learn and remember a concept. The mere act of writing something down helps students remember things so much better. If a teacher has students copy down notes as they listen to a lecture or as they read, the students are more likely to retain the information than if the teacher just gave them a copy of the notes. If a teacher has a student write a summary of what they learned that day in their learning journal, the student is more likely to remember what he/she learned. William Strong describes this process in this way:

Careful writing forces me to be explicit about what is implicit—to spin out my meanings in detail. Like a spider, I must create out of myself—without any outside intervention—what something means to me…It’s by making words known to myself and others—fashioning personal knowledge—that I learn what I didn’t know I know” (163).

And the more ways that new information is presented to a student, the more interactions the students have with a new concept, the more likely they will learn it. For example, in science, a teacher shows his students a diagram of the water cycle with no labels. He has the class describe what is happening in the diagram. He then goes through the diagram and explains it as he labels each piece of the diagram. The students copy down the diagram and labels in their notes and add small notes when they have experienced that part of the water cycle (getting caught in a rain storm, watching a river rush by, boiling water on the stove, etc.). He then assigns the students into groups and has each group read a short article that relates to one of the parts of the water cycle. The groups then present a short summary to the class of what was said in their article. To sum up learning about the water cycle, the students write a short children’s book about the life of Dewey the Rain Drop. In this example, how many times have the students interacted with the new content they are learning? Using writing along with other learning tools, the teacher was able to address a variety of learning styles and to really uncover his content for his students.

The writing to learn possibilities are endless. For example, Dean gives ideas such as:

Listing and freewriting can help students prepare to learn new information as well as to articulate what they have learned. Note taking and summarizing can help students remember and make sense of what their learning. Dialogue journals and poetry can help students reframe learning to reinforce it or find new areas of inquiry (2006, p. 34).

She also lists writing ideas such as learning logs, written debates or dialogue, exit/admit slips, first-thought free-writes, written directions/instructions, stop-n-writes, summarizing, unsent letters, listing, clustering, KWL, and biopoems (2006, p. 33-34).

Writing to learn activities can be as extensive or basic as needed but shouldn’t be used as busy work. Strong gives ten writing assignment design principles. Among these principles, he suggest that teachers choose topics that encourage inventive thinking, create assignments that are purposeful and meaningful (we should ask ourselves what kind of writing we really want our students to do and whether we would want to do the assignment ourselves), be creative but also choose topics that elicit specific responses, etc. (2006, p. 98-99). As teachers begin to design writing assignments for specific purposes, they will begin to see specific results from their students.

Conclusion

As you have read this article, hopefully you have found some ideas for developing a writing across the curriculum program at your school. Writing across the curriculum is beneficial to student learning and can be done effectively. As you apply these principles in your school and classroom and as our attitudes about writing shift toward writing as a tool rather than writing for assessment or busy work, before long, perhaps you might hear a conversation like this:

A math teacher and a P.E. teacher walk out of a faculty room, and this is their conversation:

“Ever since I’ve had my students fill out exit slips at the end of class, I’ve really found direction in what and how I’m teaching. I have them write down any questions they have and what still confuses them, then the next day I address those questions. I feel like I can help them so much better now that I know what their questions are,” the math teacher says.

The P.E. teacher nods. “I’ve had my students keep a health journal at home that they bring on Fridays for check-off. They keep track of what they eat and what kinds of physical activities that they do, and at the end of the week, reflect on small changes they can make to be healthier. I think it’s really got them thinking more about being healthy-eating right and exercising. And my class has become more than just running laps to them. Their really starting to see what it means to be healthy.” The P.E. teacher looks around to make sure there aren’t any English teachers near-by. “I’ve also been doing some writing myself…”

The math teacher smiles, “Yeah, I know what you’re saying. I guess it’s not as bad as we thought it would be. You should have heard us laughing in my math classes yesterday as we tried to write a mathematical proof showing why freshmen are mathematically inferior to seniors. Laughing in math class, who would have thought…”

References

Dean, Deborah (2006). Strategic Writing: The Writing Process and Beyond in the Secondary English Classroom. Urbana, IL; National Council of Teachers of English.

Ray, Katie Wood (2006). Study Driven: A Framework for Planning Units of Study in the Writing Workshop. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Spandel, Vicki (2005). The 9 Rights of Every Writer: A Guide for Teachers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Strong, William (2006). Write for Insight: Empowering Content Area Learning, Grades 6-12. Pearson Education, Inc.